The 27th Constant

In the wide world of physics, it’s commonly held that there are 26 constants that build and describe the world around us. These constants are important, as we are creatures that operate within observable parameters. These laws and rules are the yardsticks we can apply to worlds unseen to transform the theoretical to reality.

However, it would seem the professors and scientists of our universities and research departments have made the grave mistake of omitting the 27th constant.

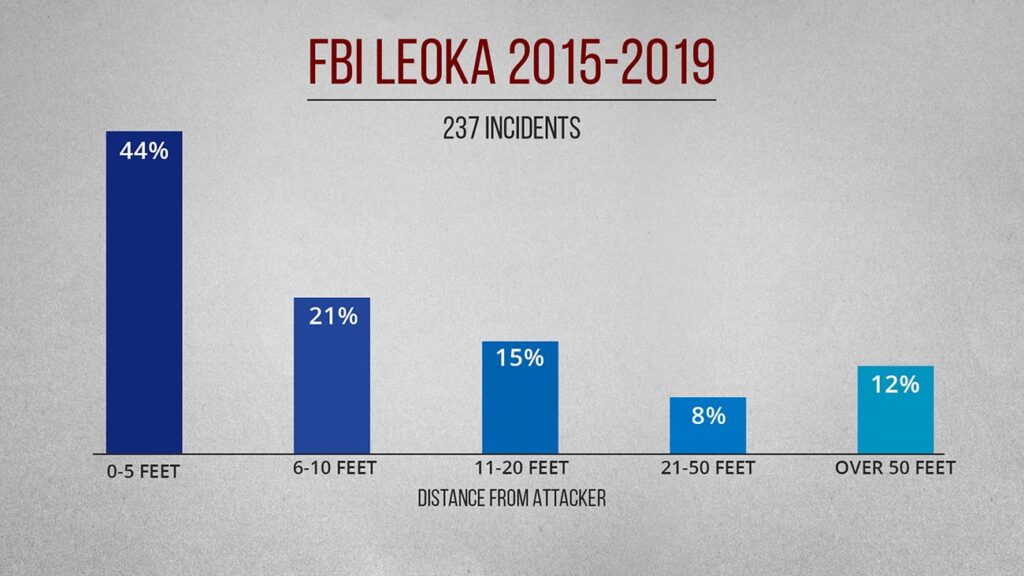

Seven yards is the constant by which the self defense world is constructed. For years, the ‘7 yards’ dogma has been repeated as the average distance in which a handgun shooting occurs. The origin, I’m told, is from FBI studies of police and citizen shootings. I found this statistic on The Firearm Blog, Shooting Illustrated, the NRA’s site, Lucky Gunner, and many other websites. It was stated without citation, which shows that the number has become accepted with such ubiquity that showing the work is something the community no longer demands.

It took some digging, but I was able to source the FBI study from 2012 that spawned the oft repeated distance.

Erroneous Extrapolation

Yes, the most popularly cited statistic in the concealed carry world does not come from concealed carriers. It comes from cops.

Which isn’t to say that the information is useless, but we are heavily concerned with context here, and if the context of shootings with police officers is to be cited, it should likewise be considered in its differences with citizen encounters. However, one should feel safe in extrapolating the idea that dealing with violent people at handgun distances should present similarly with or without the uniform, right?

Perhaps, but considering the number doesn’t even agree with itself, I do carry some skepticism.

From the same FBI release from later years, probability seems to dictate that shootings that result in fatalities are more likely to happen at distances in which I can sneeze on someone than any other. 21 feet, or 7 yards, is the least likely category by that chart. Our figure of mantra is completely contradicted, seemingly.

Some of you who’ve taken statistics are certainly bemoaning the presentation of that data, because the mean distances of all shootings will, of course, errantly skew towards the extremes so long as extreme data points are considered in the metrics.

Which illustrates a good point. Here are a few ways in which you can achieve a 7 yard average:

- 5 shootings at 1 yard, 5 shootings at 13 yards.

- 5 shootings at 3 yards, 5 shootings at 11 yards.

- 1 shooting at 43 yards, 9 shootings at 3 yards.

All of these average to 7 yards, yet none of the actual shootings happened at 7 yards. And if the above graph is used to corroborate, it seems at though the fewest percentage of shootings happen at that distance. Said as bluntly as possible: it’s entirely possible that the distance accepted as the universal standard is a total fabrication of statistics.

Measuring Unicorns

Gun homicide accounts for 12-15,000 deaths per year. About 3.5 Million died in 2021. So 0.004% of annual deaths, roughly, are from gun homicide.

We’re talking about an event that’s less than a percent of a percent. So the question becomes, then, what is the utility in adhering to the idea of averages in a, statistically, near impossible event?

Obviously, we don’t think there’s much utility at all.

In recent fame, Jack Wilson shot the would-be mass shoot at his church at a distance over 30 yards. Perhaps comically, but also grimly, the Dicken Drill asks the shooter to launch 10 rounds at 40 yards in 15 seconds. Because that’s what actually happened in an Indiana Mall when Mr. Dicken used his Glock to stop a shooter.

When was the last time you’ve heard someone cite the average elevation of a person hit by lightning? Or the average distance from shore of someone bitten by a shark? What was the average time of day in which jackpot lottery tickets were won? Food for thought.

We are trying to prepare for the worst. This is our enterprise. We understand that, statistically, we should never encounter a shooting. But the saying goes, “when shit happens, have the right shit.” We are posturing ourselves purposefully against the absolute length of violence we can realistically encounter; so why make decisions NOT based on the extent of what that may require?

What We’d Advise

First, practice at distance. The three most active contributors here (Aaron, Gino, Jake) all regularly practice with their concealed carry handguns at 100 yards. Of course, this is not to say that encounters at 100 yards with a handgun are to be expected, but neither are gunfights in general. The ability to regularly hit at 100 yards during hard practice makes the adrenaline-filled, “oh-shit” feeling shot at 40 yards much more manageable. Skills break down under stress. The best way to improve your time running a mile is to practice running two.

Second, carry enough gun. Recently we’ve been introduced to the “new era” of ‘practical’ 22lr carry. People say it performs in gel to the FBI penetration standard. Meh. Gel isn’t a human body. There are two EMT licenses and 30 years of contracting/military experience between the aforementioned three, and none of us would venture to call gel an accurate allegory of how bullets behave in bodies. I once watched a squeamish person bounce a 380 ACP off the side of an injured whitetail’s skull at a distance of 3 feet because they didn’t hit ethically perpendicular. Gel tells me 380 FMJ penetrates adequately. Meh. This is all, of course, without even mentioning barrier penetration.

A contingent requirement is “carry a functional gun”. Everyone has a different opinion on what this means, but here’s a challenge: Shoot out a barrel before you form an opinion. By the time you’re 15-20,000 rounds deep through your handgun, you’ll know a lot about it. If you’ve thrown a thousand rounds through it and figured it’s good, consider that ALL machines have mechanical parts that deteriorate. Finding the rate at which they fail is important if you’re serious about the discipline.

Third, practice your splits. The saying is often “smooth is fast.” Nah, fast is fast. Smooth, progressive practice is a method to achieve actual speed. Handgun cartridges require exact placement or great volume to be effective threat-stoppers. Graduate beyond your slow-fire groupings. Practice from the holster and practice launching shots in volleys of three rounds and up. If you’re going to shoot once, you should then shoot until the threat is stopped. In for a penny, in for a pound. We assume you’re always going to shoot only in defense of life, so don’t stop shooting until the threat to life has stopped.

Lastly, start incorporating movement. Many defensively-oriented drills are done in a stationary manner. Of course, finding cover and concealment when bullets are flying is something you’re going to be highly interested in doing. Once you’ve achieves basic and safe competency with a handgun, start doing all your favorite drills on the move. Whether it’s lateral to the threat, retreating, or even just changing levels, add in some movement to your practice. Develop that automatic response.

If you can slap 5 rounds onto a 50 yard target from the holster in under 10 second and end up at least 5 yards from your starting point without a miss, you’re a savant (or maybe Gino). It’s a difficult measuring stick, yet a worthy level to strive for.

Why? Well, because…

We’re worried about catastrophe

And we want to be prepared for the extent of that catastrophe. Preparing for only 25% of catastrophe sounds silly, doesn’t it? Yet ‘average distance’ statistics and gel results talk people into doing exactly that every day. Now is a good time to draw from “Tier None” and the punnet square discussing the frequency of emergencies. We often have an entirely unrealistic notion of how frequent they are or how much time we need to invest in particular skills.

Consider all that when you encounter the guy that only ever practices at 10 yards because “well, it’ll likely happen at less than 3 yards anyway… I won’t even have to use the sights!” He’ll cite statistics. He’ll feel justified in that. You’ll know better.

Revolver guys tell you that most shootings resolve in less than 3 rounds. Except for the ones that don’t.

Sure, the majority of shootings happen at sniffing distance. Except ones that don’t.

Having to use your concealed carry is an exception. Thus, you should prepare for the exceptions.

As always, thanks for reading.