This article is rather overdue, we realize.

The term ‘Hyperoptimization’ has been referenced in a few other posts on the site and Patreon, but we’ve left you without a solid explanation. The term itself bears some obviousness that we hoped would carry it, but part of the reason it took so long to get this written is the depth for which the rabbit hole goes.

Perhaps the best way to explain what it means to use is you take you through the historical evolution of how we’ve used the term ourselves. Originally, it began with a simple quote idea. After adding in a caveat or two, it started to balloon into a much wider topic that encompassed more of our thoughts about the relationship between gear and skill than we thought.

Truly, that’s what Hyperoptimization as a term has come to convey. It’s not just about gear discussion in a vacuum, but gear as it pertains to both the job and the person doing the job contextually. We’ve had to reconcile a view on gear that understands why top units pick the gear they do, but also why it’s so nerdy when overweight Instagram larpers buy the same gear.

Where it Started

Originally, Jake had come up with the following:

Hyperoptimization is when adequate answers are considered inadequate because better answers exist. A 90% perfect solution existing makes an 85% perfect solution seem suddenly 0% perfect in the eyes of the hyperoptimized thinker.

While this may be true, there exist many contextual counterarguments. One of the main include the idea that accepting mechanically inferior solutions is an illogical sacrifice. You’ve probably heard somewhere in a concealed carry community “I want to have every advantage that I can.”

That idea makes sense in a vacuum. But, you know us by now. Vacuums aren’t where we want to live. We harp endlessly upon the soap box of context.

So the Roland Special guy tells the stock Glock 19 guy that they want ‘every advantage they can.’ If that was said by an ex-infantry USPSA Grandmaster, it’d sound reasonable. But what if it was said by a 350lbs guy who can’t hit a B8 at 25 yards? Feels different, right?

“Dude, a Glock 19 is more than fine.” That can sound true in a vacuum, too. You’d accept it from the prior 18B competition shooter, but would you accept it from the obese guy who can’t shoot? Probably not.

You might argue that the idea should be divorced from the person that utters it, but we cannot. The experiential wisdom behind advice is inseparable from the advice itself, we believe. Just like your math teacher made you show your work, we care as much about showing the world what led to an opinion as the opinion itself.

And so, we needed to change the framework of what we considered ‘optimized’ to include an array of understandings and skill levels.

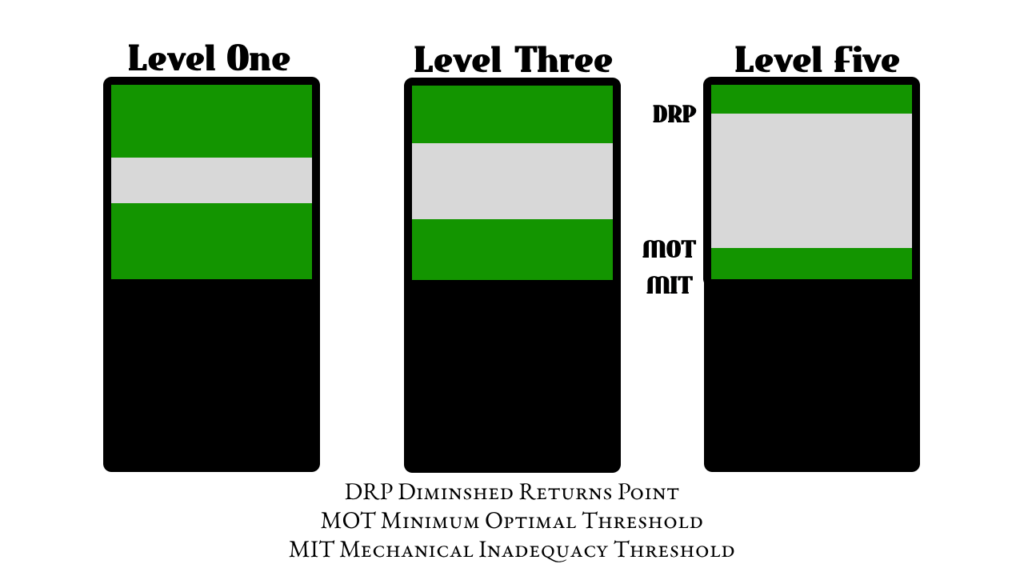

The Graph

Some explanation:

Levels refer to the 1-5 scale in which we grade skills in our skills audit. For a full understanding, please reference Collecting Hammers. Quickly, Level One is a true novice, Level Five is a true expert – the rest range accordingly.

MIT: Mechanical Inadequacy Threshold. This is the point for which everyone, regardless of skill level, must surpass in order for a tool to be considered viable to complete any task. To keep our carry gun example going, this where unreliable guns get disqualified from consideration; or guns of insufficient caliber. While a 25ACP mouse gun could maybe stop a threat if the planets aligned, it does not do so with sufficient force, reliability, and other contextual factors that it’s even worth considering for adequate daily carry. It does not matter if you’re Level One or Level Five as a shooter, gear options below the Mechanical Inadequacy Threshold are a non-starter.

MOT: Minimum Optimal Threshold. This is the beginning of the ‘optimal range’ for any job based on skill level. Meaning, this can be lower or higher for different people. Smack in the middle of the optimal range is likely a factory Glock 19. Lower on the range, while still being above the MIT, may be things like larger DA/SA handguns. A Sig P229 is larger and heavier to carry, requires more training to master the double action pull, and may carry only 10+1 rounds of snappier 40SW. Objectively worse? Probably. But to someone who’s an expert, drawing and putting two rounds in the bullseye ring at 7 yards with either gun would probably feel like a trivial difference. To someone in which the P229 falls below their MOT, it will feel considerably more difficult.

DRP: Diminished Returns Point. This is where mechanical advantages stop yielding benefit due to the skill ability of the user. Finite differences in trigger or sights can make a big difference during a master-level competition run to the expert shooter. However, the difference between a Zev Glock and a purely factory Glock 19 to a beginner shooter is mostly lost on them. They haven’t built up the skill required that allows the mechanical advantages to materialize into better results.

This Explains a Few Things

First, it explains why advice from people of advanced skillsets can vary. Master Shooter #1 will show you how much tighter their groups are with that Zev trigger job and a Trijicon SRO on top of their Glock and tell you that the advantages matter. Master Shooter #2 will take a completely stock Glock and put up a group that’s 90% as good as Master Shooter #1 and claim that skill is what truly matters.

Who’s right?

They both are, in a sense. What would really make the difference is knowing who they were giving the advice to. If their class was full of guys who shoots weekend matches, spends a couple grand on ammo annually, and trains pretty regularly; yeah, maybe Shooter #1 is speaking more contextually appropriately. If this is a course aimed at beginners who have the budget to sling maybe a couple hundred rounds every few months, Shooter #2 preaching about dry fire is going to be more contextually appropriate.

The lesson here? Know the audience and their context before judging advice. Know the experiences that yielded that opinion of the advice giver. Understand if they’re contextually aligned in goal.

Advice without intent towards audience is useless. Imagine you were looking for insight on how to deal with home intruders. Now imagine that a dude who mostly fought in a jungle told you that the best way to deal with your staircase is to drop a JDAM on it. Like, “wow, thanks for the fucking insight, gramps.” You’d be right to roll your eyes. But people parrot that value often. People who were never in positions to ever utilize close air support included. It’s advice loved by people who cannot take it. Alanis Morrisette, is that you?

That’s the second thing it explains; why people who have never done something feel so comfortable telling you how to do it.

Because advice seems like it can be offered in a hyperoptimized vacuum, people often think they’re reciting cold, hard fact. Like they’re reciting a definition from a textbook in class. They could not tell you who discovered the phospholipid bi-layer, or how it’s different from plant cell walls – but they can declare with full confidence that YOU have one. In fact, you have many. In fact, all animals do.

Now, is that actionable knowledge for them? Probably not, unless you were discussing the differences between how a virus affects you as opposed to an oak tree.

It’s the mindset that leads the brand new Lieutenant to cite a cold-war era infantry manual to his thrice deployed Platoon Sergeant and think he’s making an inarguable point. It’s why airsoft kids can watch GBRS and think that footwork is the big secret to good CQB. There are lots of subjects that exist above the Level One DRP or below the Level One MOT that just require the experience to learn how to contextually apply. However, because Level One dude heard it from Level Five dude, they think it’s gospel. If they put in the work to get to the advanced levels, they invariably learn that it’s not.

Lastly, this explains why we accept an array of viewpoints from experts but reject the exact same opinions from a novice. Despite the advice being identical, subconsciously we cannot divorce from the advice the experience that informs it.

Finally, the Definition

Hyperoptimization: the insistence on a hardware solution that one has not developed the software to contextually apply.

It’s important to note that this works two ways. A beginner shooter may say “You don’t need a red dot!” and then also say “A Makarov isn’t good enough for concealed carry!”

Are they wrong? Not exactly. For who they are as a shooter, and if speaking in terms of themselves or other beginner shooters, they may be more correct than incorrect. If you’re a more advanced shooter, you’ll probably disagree with that guy, and you should disagree with them, because you’ve put in the work to 1) raise your DRP to take advantage of the advantages a red dot gives and 2) lowered your MOT so that you could make accurate hits agnostic of platform.

The Big Point

The point of advice or recommendations is to help people.

Removing the context of that person’s situation and skill level from the advice is the opposite of help.

We understand that much of this seems self evident. But prior to the 1670’s people knew that when you detach an apple from a tree, it falls to the ground. Newton’s description of the mechanisms of gravity are ultimately more important than a surface level understanding of the concept. That’s what we’re hoping for this article to be.

We write things on this site with an audience and end-user in mind. To do anything else is an vanity effort. And you can see that rife in this community. What skateboards and sneakers have to do with helping people defend their selves and loved ones, I have no damned clue. But be sure that they’ll have a logo on it, and they’ll be selling the same solutions to people of different levels regardless.

As always, thanks for reading.