Hurricane Ida: An Inside look at the Disaster

Introduction

Hurricane Ida rolled in on August 29th, 2021, 16 years to the day after Hurricane Katrina. The last time a storm this strong made landfall, I was sitting a hotel room, waiting to go to MEPS the following day. Within a couple months, I’d be in Biloxi, looking on some of the most ravaged landscape modern American had seen to date.

Flash forward 16 years, I couldn’t help wondering what I was getting myself into driving south as Ida made landfall. I watched the weather change as the first of the spiral bands lashed me with wind and rain in Arkansas, and I’ll never forget driving past McComb and thinking I should stop at the next town. The next town, Magnolia, I’d pass through just as dusk overtook the waning light in the wake of the storm, and I’d look down on the streets, gray and without power, and think “well, that’s that.” There would be no fuel here, and there would be no fuel for days afterwards.

What would follow wouldn’t have the same impacts as Katrina, but I’d hear a common phrase time and time again in the wake of Ida:

“The flooding isn’t as bad, but the power infrastructure is worse.”

The Backdrop

Anyone who has been to NOLA knows this already, but it’s a gritty, loud, sweltering swirl of parties and poverty; of culture and crime. Hurricanes are national news, but locally, they’re just another feature of life in the ‘Guff. Said another way, the people are tough, and so is the landscape. When one of the other members of my team thought they saw a body on the side of a flooded road on the outskirts, they stopped, got out, and turned their flashlight to an enormous gator. By the next day, the locals were pulling off the ramps and casting lines just off the freeway to see what they could catch.

Even with a culture of toughness and self-sufficiency, though, Ida would prove to be a challenge. Not only was it blisteringly hot and humid, but it became immediately evident that the effort was going to take weeks, not days to restore power.

Closer to Home

My trip to NOLA was business, not pleasure. The client generally does an exceptional job taking care of us, but this time was a bit different. Sweltering, moldy-smelling rooms. No food apart from fig bars for the first 48 hours. No fuel for the first 72 hours, and frequent trips of 60-140 miles put a strain on our resources. The roads were congested as frequent wrecks, debris in the roadway, and people running out of fuel blocked the interstate. Downed power lines and abandoned vehicles created blockages on the sodden roads. Homeless camps popped up under many of the parking garages and overpasses downtown.

We were there to assist with the recovery effort, but that didn’t put us outside the disaster, or the threat of needing recovery ourselves.

Gas and Power

It didn’t take long for the first people to start running out of fuel. Those who’d put it off, or thought the storm would pass quickly found out that what they had was what they’d have for another week. About a week in, lights started popping on in small spots in the city, an island of light in a sea of darkness, just long enough to power a station for a few hours.

For those of us who brought extra fuel, security was a constant issue. The first day gas was available, there was a shooting between some dudes waiting for fuel. Quite a few of the other vehicles that were well set up for the disaster had roof racks with jerry cans, but those were visible, and with most of us doing 16 hour days, all we could do was hope that the local police would keep people at an arms distance from where we were posted up.

Power Production

Beyond that was power. Many people planned around their car as a sort of mobile power station to charge their phones and laptops, but the process was long and required burning gas, which was running in short supply by day two. It can be tough to mentally flip that switch and say “this is what I’d normally do, but this isn’t going to be normal…” and for those that didn’t, the learning curve was steep.

These situations are relevant for a few reasons. Not only are they *very* common, but they were all things that we discuss within the broader framework of Sustainment. As we’ve discussed, a “bug out bag” is largely useless to most people unless they evacuate well ahead of time, but sustainment is the idea that you KNOW there will be hard times, and you’re not going to be caught flat footed.

“If you don’t bring it, it won’t get there”

I was able to bring an extra 25 gallons of fuel, my sustainment bag plus all my kit for two weeks in the Rover. The Aukey portable 30,000 mAh battery bank was easy to recharge while mobile, and provided days worth of power for my cell, and Surefire Stiletto Pro, which is rechargeable. One major bump I did have was my lightning charger snapped clean in half. It took 3 days to find a replacement, since almost all the stores were closed. Another oversight was that I hadn’t returned a head lamp to my pack after camping recently – needless to say, headlamps in power outages are incredibly useful, especially if you’re frequently doing tasks that take two hands.

As well, I’ve long been advocating a siphon hose in an airtight container, and situations like this are why.

A stroke of Fortune

I was extremely fortunate in that one of the assignments I received brought me to a well provisioned power station. They had reserves of fuel, but they themselves were straddling the line in terms of power produced and power consumed. That meant the pumps had no power, leaving full tanks just sitting there. They also had oversized nozzles to prevent employees from gassing up on the company dime.

Eventually we hooked up a solar panel to a battery which gave the necessary voltage. However, because the nozzle itself was too big, people had to fill *absurdly* slowly… or fill a can and dump it in their tank manually. They pulled the nozzles off, and tried using funnels while kinking the fuel hose like a garden hose. That worked, but eventually we were provided with some normally sized nozzles.

None of those got much use, because of the jerry cans. If I hadn’t had them, the siphon would have been the superior option.

Reconnoitering Downtown and the Floating City

Another topic of importance is being able to speak to people who are hot, tired, frustrated, and overworked. One of the tasks I had was recon for establishing a command post in NOLA. Another was doing the diligence to establish security for a cruise ship. They converted the ship to a floating barracks for over a thousand linemen who’d showed up to work. Generally, these guys are tough and used to working in austerity. They also know the money is too good to piss away the opportunity doing some thing stupid. But this is 2021, and nothing is simple. The cruise ships required EVERYONE to be tested for SARS-nCOV19 on an ongoing basis.

Needless to say, personal biases enter into this.

Dealing with people who believe everyone should be vaccinated and another who couldn’t care less takes some delicate handling.

Command Post

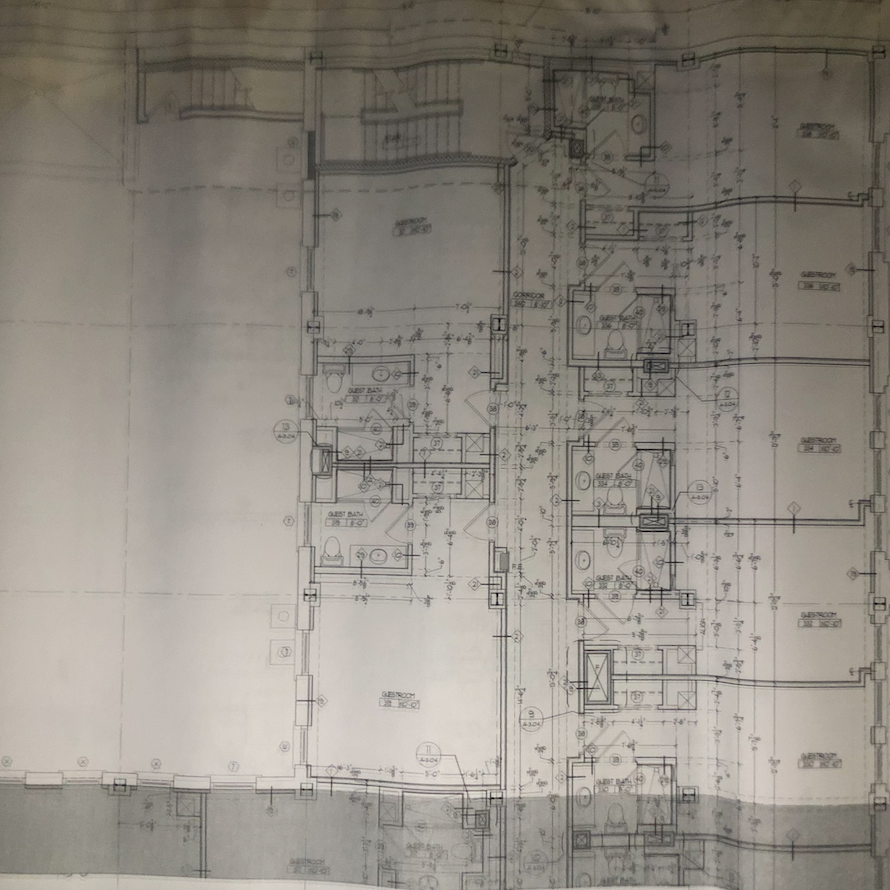

The tentative command post, likewise, was not ideal. Not only that, but it failed some major criteria; namely the ability to keep a generator near the workspace which had to be secure. Lodging another pretty large contingent required knowing the building layout. That meant security risks, capacity, which rooms could host double or single occupants, and location of fire escapes. Additionally, we’d need to know if the building had power, water, or food, etc.

Since they didn’t have a floor plan printed out, the head engineer allowed me to look over the building schematics. This ended up serving an utterly unforseen purpose, as well. Barring the use of 300 feet or so of extension cords, there was no safe place to run the generator. Looking over the schematics, we found a way to bore through a couple walls, and shorten that distance to about 50′. This made the location both secure and tenable.

Sadly, after this location was set up, there was some friction between the hotel staff and security.

The lesson here is this: plenty of dudes are good with guns. Get good with people. It’s a dying art, and it’ll help in damn near every aspect of your life.

Equipment

So, what equipment was used?

Typically, when people think about security they think guns and radios. Radios were helpful, as we had both handheld and base station units for HAM and CB. However, neither were particularly useful for information gathering this time. I can usually find some local chatter/knowledge, but without power, most information was traveling by word of mouth.

More Importantly

As the fatigue evaporates a bit, you remember that the most important thing isn’t so much the equipment as it is the people you’re working with. The ISG team and FoG (Field Operations Group) for their continued support, and providing almost constant updates both for travel and for in-situ problem solving. I was very fortunate to work with some excellent people, both on the ground, and in the mobility phases of the disaster. So, thank you to all of those who contributed.

Firearms and Holster Layout

Firearms wise, I elected to take both the M&P CORE and the M&PC, as the work would include some presence and some discretion. The main takeaway for me was the utility of the Phlster Enigma, which I’d been testing for a few weeks before as an option for more formal details. Because the Enigma provides it’s own chassis for your sidearm, it’s comfortable for work in which you’ll change posture. The chassis system is very comfortable for driving, as well. Another feature the ability to change your clothes without having take everything off your belt and put it on clothing. I ended up wearing the Enigma with the M&PC for the duration, except while sleeping. It performed extremely well.

EDC Tools

The Surefire Stiletto was a recent upgrade from Centurion Partners Group. My old light, a Surefire Tactician left me a bit ‘ho-hum’, and contrary to a lot of the gun world chatter, “all the lumens!” may make sense if you’ve got a dedicated flashlight and all you’re doing is searching structures looking for bad guys….But in real life, that flashlight is going to be used constantly for more mundane tasks.

A retina-scorching 1000 lumens under the hood of a vehicle while you’re trying to make coffee by tapping an inverter to the battery at 4 am doesn’t require that kind of output. As well, given the power situation on the ground, you don’t want to be running your light at max more than you have to. Not only because it makes you visible, but it burns through your battery reserve. In any case, the Stiletto Pro was outstanding. The variable outputs helped with power conservation and matched the illumination to the task nicely. Having a rechargeable light is (and will continue to be) *huge*. The layout made it easy to use without cycling through max or min lighting modes, which I really appreciated.

Another stand out was the SOG PowerAssist, which was handy on several occasions. A multi-tool has long been one of my main EDC items, and the ways they’re useful are countless. Especially in situations where you may not have access to good tools.

A quick ending note on equipment – we received NO money for endorsements. All of these tools were bought for our own use. We don’t see any compensation from making mention of them… they’re simply quality items that we are comfortable recommending.

Conclusion

The majority of the topics hit here are pretty common, and the way they were addressed were more or less exactly as we’ve been advocating. We had a pretty standard Type II emergency with shortages and embedded Type I’s (there was a carjacking, and a couple fights, though they didn’t affect me), and access to critical resources were compromised. In terms of sustainment, mobility, protection, and interpersonal communication, Ida further validated the ISG approach, it’s modularity, and concepts of lines of equipment.

After the first week, there was a reasonable relief for me – I had access to resources that were more or less unrestricted… but had worst come to worst, we know what works. Keep your guard up, but be good and reasonable with people. Have a plan to both supply your own sustainment, and use it sparingly. Know your physical limits in terms of food, water, and shelter, and be able to adjust to the rule of 3’s.

Above all else, suffer discomfort with dignity. Some of the best advice I ever got was as a young Airman, my mentor told me “Don’t complain. It doesn’t do any good and nobody likes it.” I’m always a little floored when experienced men in the profession of arms gripe over the stuff we’re all dealing with. It doesn’t do any good, and nobody likes it. Stay sharp, flexible, and remember – it’s not your disaster.

Cheers,

Aaron