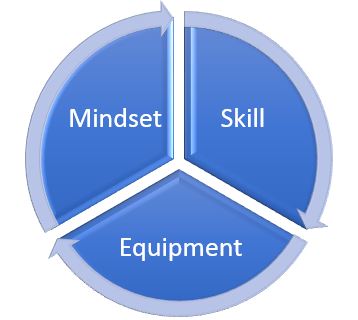

There’s an adage in skill building: There’s Software and Hardware. Does this analogy really do the situation justice, or is there more to it? We say the latter.

Introduction

There’s a common colloquialism that there’s “hardware” and “software”. In this analogy, the body and brain serve as a programmable computer, while the tools we use enhance that computer’s effectiveness. While no analogy is perfect, we can intuitively understand the intent behind this: We must have “software”, or “skill” to think through problems and “hardware” or “equipment” to accomplish tasks.

The problem is with this is twofold: It oversimplifies how complex training is, and it sends the wrong message to people who are in the early phases of their development.

Chances are, if you subscribe to our work, you already get this and agree, so what we hope to do is:

- Give you some talking points to plant the seeds of higher competency in the minds of those still in the early phases of development, and;

- To give the those same guys and gals a place to go to give some honest reflection for if/when they’re ready to get serious.

- Make the case that the most powerful tool in the human arsenal is mindset, and that the Hardware and Software mode of thought is incomplete without it.

While we try pretty hard to be cool when we call people out, it’s time to acknowledge that most of what is being sold for self-reliance just selling hardware.

This isn’t golf where having the most expensive clubs gives you status. So don’t fall for Crate Club’s “May cause Manliness” pitch – you can’t buy your way to masculinity, and in this article we’re going to put a point on a simple truth:

Buying your way to an image is never cool, you’re going to have to put in work.

‘Masculinity’ is more than just playing dress up or buying stuff, so when you see pitches like this, remember: They’re the opposite of what we’re looking for.

We want you to build yourself into a useful, capable person… Not pitch you an image to emulate. We want you to build yourself into your most effective form. We want you to have self worth, skill, and critical thinking… not to admire that as some distant, unreachable goal.

One of the first steps in doing that is establishing the intellectual framework necessary to make good decisions about your skill development.

The Fallacy of the Analogy

– No one

The Hardware/Software analogy doesn’t account for the reality of human learning: we aren’t simple GIGO (garbage in, garbage out) computers; we learn through experience and we’re hardwired with instinct.

Further, with experience we can develop accurate, contextual, and relevant solutions which facilitate our ability to build relevant skill. We can use these experiences to validate that our approach is effective in ways machines cannot. We can question prior learning, as well.

Said another way, the human experience is about both individual learning and experience, and cultural success.

Habits and practices that are successful are enduring, while those that aren’t are relegated to the book of infinite dead. In that way, we advance most when we test our practice under pressure.

The “hardware and software” approach doesn’t include these aspects of human capability, and it likewise excludes verification.

Without verification through pressure testing, it’s impossible to determine what works and doesn’t.

Speaking plainly: Without mindset (the result of experience and will power), skill and stuff fail take into account the true strength of human kind. Mindset.

Trying to explain how to develop skill by using the “Hardware and software” analogy is like trying to explain how plants grow by saying “water and sunshine”. It’s not wrong, but it’s certainly not the full picture. We need to include mindset, which is perhaps the most important determining factor in success or failure under pressure.

Necessity

The emphasis we’re placing on mindset shouldn’t be taken as a slam against skills and equipment; just the opposite. It’s a complementary quality.

Most skills are built upon the use of tools. Whether it’s carpentry or shooting, having the right tools makes the task something more than just a wild gamble. This makes skills and tools a natural combination and it’s easy to overlook that mindset is as important in making our efforts pay off. First, let’s look at what’s required of our individual parts, so we can put them all back together.

When we discuss tools, we require three things:

- Reliability – The tool we select needs to be capable of repeatedly working without mechanical failure.

- Efficiency – Whatever it is, the tool should be efficient at what it does.

- Durability – The tool should be able to withstand physical abuse without detriment to points 1 and 2 above.

What we ‘want’ from our tools should always include these three points first. If we build from this point, the question of equipment will be simple, and we can turn our attention to the more pressing matter. How to bring skill and equipment together with mindset to become an effective problem solver, rather than just someone who can use a tool.

Skill Bridging

When we discuss skill, things become a bit more complicated. Skill Bridging is a concept we use to test whether or not a thing makes you more capable or not. This, in turn, can help you to determine if you should dedicate yourself more to the technical aspects of skill development, or place more emphasis on becoming skilled with a tool. Essentially we want to answer the questions:

- Does this piece of equipment do something I cannot accomplish with skill? (Skill)

- If I were to find myself without this item, could I work around the material deficiency? (Mindset)

- Is there a piece of equipment that makes the task substantially easier? (Equipment)

Once we evaluate a problem using this model, we should be able to establish:

- The best practice for solving the problem

- The best equipment to facilitate solving the problem

- The best way to employ equipment and skill to optimize the outcome.

With medical equipment, there’s plenty of ways to illustrate skill bridging; stopping bleeding, for example. Sufficient knowledge and technique can allow a medic to stop arterial bleeding by using pressure points. However, this dedicates all the medic’s efforts to maintaining those pressure points until the patient can be stabilized. If there’s only one victim, that might be OK, but what if there are other serious points of blood loss? Other Victims?

A tourniquet is a piece of equipment that can accomplish the same task (stops the bleeding) while freeing the medic to attend other problems/patients. The tourniquet bridges the medic’s skill and allows him to work reliably with greater efficiency and without risk of equipment breakage. For that reason, the tourniquet is a better option than skill alone, or skill and improvisation.

This highlights a subtle principle we can tease out:

- There are items that enhance your skill, overcome natural inabilities, and are required by a certain skill-set (such as shooting… doesn’t matter how good you are with a tool if you haven’t got one). This also means we should have a backup plan.

- There are skills that can be used without tools, with varying degrees of effectiveness.

- The logical outflow of these lines of reason converging is: Having skill allows you to assess your shortcomings and effectively employ tools while having the right tools facilitates your ability to effectively solve problems.

That’s actually pretty important. Without enough skill or proper equipment, an effective outcome will be an island. We can apply this from everything to what we carry to structuring our training to get the most from our efforts.

Computers (at least the ones we know about at present) can’t skill bridge. They can’t take programming to, say, win Jeopardy, and use that same knowledge to be better at Chess. They can’t solve complex problems. We aren’t computers, and we can learn to do a variety of things well. The more you know about one subject, the easier it is to appreciate the discipline necessary to succeed in another. To borrow from Musashi:

“To know 1000 things, know one thing well.”

Best Practice vs Outcome Based Problem Solving

A while back, we had some criticism regarding using the blade of a knife on a magnesium fire starter. The criticism (rightly so) is that eventually, that will damage the blade.

They’re right: it can.

But are we missing the forest for the trees by focusing on that?

When we face a problem, we have paths that lead to solutions. Tying this back into “hardware and software”:

If we think of best practice like programming, and define only a specific way to use our tools, we’re limiting the paths we can take to a successful outcome.

Your ax can be used to pry doors open. The blade of a knife can be used to start fires, often quickly, efficiently, and the risk of damage is only with prolonged use.

Here’s what we’d like to submit for your consideration:

Problem solving for the best outcome is more important than rote learning for ‘best practice’.

What we have in instances like this is irreconcilability of programming and outcome based problem solving.

We’re indoctrinated into thinking that best practice means deviations are met with dire consequences, but that sort of inflexibility is the exact opposite of what we need in dire situations: adaptability.

It doesn’t mean you should throw best practice out the window – it exists for a reason, but this is a solid example of where mindset is excluded, and how it can handicap outcome based problem solving.

If we look at this another way, let’s say we have a house fire, and we have 3 minutes to get out. The doors are blocked, and you’re trapped inside. There is a window. Windows are meant to be opened to facilitate air exchange. If you break it and climb through, that’s not best practice, and it’s not what the window was meant for. However, what’s considered best practice for using the window is secondary to not dying of a thermal injury. As such, who cares if you eventually need a new window if your choice is between breaking it and dying?

- Stuff changes based on context. What’s best practice under ideal circumstances isn’t always best under real circumstances.

- Institutional knowledge has a lifespan. Trust, but verify. The strongest verification comes from practice.

- Don’t be afraid to test different practices.

- Fail fast; if you test some other method and it doesn’t work, don’t remain committed to a bad idea.

Bottom line: You’ve got to live long enough to care about the knife.

Conclusion

To tie this all together, when we approach skill development with a mentality of “hardware and software”, we reduce this concept to a point at which there’s no room for critical thinking. Without asking the hard questions, and committing to thorough, considerate testing, ‘best practice’ is largely just institutional inbreeding. Best practice changes with technology, technique, the problem presented, and context. So set aside some time to do more reading, go out and gathering experience, and don’t be afraid to question the experts or test your gear until failure. More importantly, don’t limit yourself by programming in ‘preset solutions’; think through each problem as it arises. Consider what you know about the circumstances, your level of skill, the available resources, and the risks involved in your plan.

Firmly plant yourself in the understanding that Emergencies occur on timelines, and we have to address them from the shortest timeline to the longest; the most pressing concerns get addressed first.

Finally, and probably most important: Fail fast.

If your approach or group isn’t working, switch out. Don’t stay committed to failure.

Cheers,

Aaron