Relevance in skill building is one of the most important things you can establish; make sure what you train your body to do is actually effective and practical.

Introduction

ISG was created for a number of reasons, but perhaps none of them are so important as trying to help fill the void of relevant, actionable information for resilience.

Time and time again, we hear things that people say that show they just haven’t quite got it yet. In the age of the cyber hate engine, it’s easy for these people to get lost, isolated, or simply scorned for this. However, the vast majority of people jumping on the dog-pile don’t know what they’re talking about, either. All this makes learning difficult if you’re new.

Let’s cut to the chase: You need relevant information to make good decisions. Relevant information, especially in a life or death pursuit like gun handling, medicine, or martial arts, requires experience. In this article, we will discuss how to gain experience, relevant information, and in the end, how to put it all together to make sure you’re not stagnating.

The Experience Cycle

People pass through phases as they learn. There are three key points we want to push forward here, so let’s put the bottom line up front:

1. Knowledge shows you your ignorance: The less you know, the easier it is to be confidently wrong. The more you learn, the more you realize that there is an incredible wealth of information out there, and you’re not as smart as you thought. This is good.

2. Goethe said: “When we treat man as he is we make him worse than he is. When we treat him as if he already was what he potentially could be, we make him what he should be.” We need to treat others as if they will eventually become competent. If you *do* know something, treat people in such a way that they reach their potential (when possible).

3. You might quit, but you’ll never finish.

The following model of learning called the 4 Stages of Competence describes this well:

1. Unconscious incompetence

2. Conscious incompetence

3. Conscious competence

4. Unconscious competence

We could spend days unpacking all of the above, or we can combine them and say the following: You don’t have a lot of time to get good, so let’s not spend it fooling ourselves or belittling others.

Let’s pick up the ball and get to playing so when we play we are a benefit to our team, and can strengthen others.

Experiential Learning

What very few people in the profession of arms will tell you, but what they all know is that position or title is no guarantee of experience. Experience – especially with gunplay – is rare. It’s hard to come by. If we accept that “Spheres of Violence” is correct, having experience in shootouts as a Marine infantryman doesn’t make you an expert in dealing with a shootout at a gas station that’s being robbed. There are contextual differences, and there’s no perfect 1:1 translation between experiences. This is further complicated within martial circles because it’s nearly impossible to practice a lethal art outside of very controlled environments.

So how do we get experience?

We train.

Training is experiential learning. Every time you engage in a skill based activity, you’re gaining experience. When we experience things in the training environment, however, they don’t always translate well to reality. This has given rise to the most absurd, desperate, and inane argument in martial arts: the “in da streetz” argument. As it goes, people who’ve been in street fights laugh at martial artists as essentially playing a game, while martial artists mock people with only street fighting experience as boorish. It shouldn’t be a surprise that both sides are right and wrong, as it’s entirely possible to ‘win’ a real world fight and know almost nothing.

What matters here is how we train, and recognizing that while not everyone can go get in street fights, an MMA gym is a reasonable substitute that will improve your fitness and familiarize you with violence. People who’ve done some street fighting (I’m one of them, regrettably) are a bit more clued in on the social indicators that precede a fight, and the fallout from getting involved.

Both have valuable lessons to teach, and both can accept that the other has viable information. If you don’t, see point 1 in the experience cycle.

Diminshed Returns and Overtraining

One of the problems with training, as opposed to experiential learning, is that training is a controlled environment. Real life is an infinitely more complicated place. Therefore, it becomes easy to trick ourselves into complacency by focusing all our attention on one skill. This is extremely common with shooters; they view the gun as a solution to every problem. Often, there were a number of indicators that we can observe if we train ourselves to look for them.

As well, there are times when drawing a gun – even in a lethal force encounter – is a poor option due to a disparity in skill, strength, or numbers. When we overtrain in one specific discipline, we begin to lose sight of other, equally important skills (such as Applied Situational Awareness, or an understanding of violence) and we objectify the tools, rather than resolve ourselves to starting over as unconsciously incompetent beginners in a new field.

Said simply – we default to the skills we think will provide us the greatest chance of success. If we build in one skill to the extreme, we may be leaving out others that are better suited to resolving the problem with the best outcome.

Relevance and Practicality

In the past, we’ve discussed in great detail how certain professionals who have strong credentials present information that is pretty bad.

The reason is usually: it’s not relevant or practical. In a recent example, a fit, 200 pound man with a knife accosts a woman on a swing. In defense, she pulls his beanie over his eyes, and pokes him in the neck with a stick. A stick. Not a stake or something. He rolls over, presumably in agony and confusion, and she gets away.

We don’t want to get hyper critical about the instructor, but this is important. In the age of 3 second attention spans, we need to keep expectations real, not entertain people with fantasies.

Real bad people don’t stop cause you poked them in the neck with a friggin’ twig. My experience is when you fight back, they hit harder. Let’s just stop playing make believe, and admit that if you’re a 100 pound woman, and a 200 pound dude with a knife gets the drop on you, it’s likely curtains, and you’re now going to be forced to fight a major headwind of illegal captivity. That’s why we constantly harp on awareness and making smart choices. There’s a certain point at which you’ve failed, and all the feel good talk about “mindset” is fluff. This isn’t to say we don’t agree with the premise of “fight until the last”, we do. But if you want that fight to mean something, you’ve got to be able to fight. It doesn’t matter how much horsepower you have if you’re stuck in neutral. If you’re not trained to control that blade, take a dominant position against a much larger attacker, and access your own weapons (that you’re carrying), it’s ‘Good night, Gracie”.

Once we admit that, we can troubleshoot how to:

- Not get to that point, and;

- Have a realistic expectation of the outcome if it does happen.

- Train in a way that gives us the best odds for an outcome we want.

Now, to the instructor’s credit – he is trying to describe a mindset solution to the problem of being accosted. His message is essentially: “Don’t give up and fight with everything you’ve got.” We can fully get behind that, and his broader message is about the will to act in the face of violence. That’s solid, but we need to be very clear about this: while compliance is never the best option, “will to fight” alone isn’t going to work.

Anecdote

A person of our team’s acquaintance was accosted by a man armed with a knife. He demanded she stand perfectly still, as he held a knife to her neck. Slow, and gradually, he began ordering her to change her posture. Lay down, stand up… and then he started cutting her. Little bits at first, all the while saying if she screamed or tried to run he’d kill her.

The moral of this story is that action – any action – probably would have been the same as submission. Ultimately he slash her throat (though she miraculously lived). But none of this preempts the fact that she was walking around alone, after dark, in a known bad area. We’re not in any way trying to say the victim should be blamed – but if we can’t take precautions, the only viable post-caution is ability. Willpower is a part of that, but it’s not the whole story. The other is using good judgment.

Efficacy

There’s another video where he and another guy – at near contact distance – discuss movement to access a firearm. Again, he outweighs the “good guy” by a solid 40 pounds. The good guy demonstrates some footwork that allows him to get to his gun into play.

The video correctly synthesizes some key points; “When weapons are prematurely deployed they become ineffective… or worse your weapons become their weapons.”

He’s completely right, but if we’ve correctly assessed a likely problem (introducing a gun that could be taken) so why teach someone to race to a draw when someone is in contact distance on the receiving end?

The reason presented is that some people don’t want to learn advanced fighting skills, but this doesn’t necessarily cross into “advanced” territory. Some very basic grappling and control over the adversaries weapon could make the difference we’re looking for, and without escalating this into a lethal force mess.

Relevance means understanding that handgun bullets don’t do amazing things to human tissue. It means knowing that if you try that, and it doesn’t work – this guy with a knife who is right on top of you has literally every advantage. So not only are the tactics he’s teaching very bad, but he doesn’t understand that what he is teaching is impractical and irrelevant in a fight.

What makes a real fight?

Well, it doesn’t end when you think it should for starters. It goes until the other person is unable or unwilling to keep fighting. The fight doesn’t care if you’re tired, can’t see, can’t breath, or you’re being stuck over and over again. It’s impartial.

Bottom line down here on the bottom: You shouldn’t want to carry a gun and not having some ability to fight without it.

There’s a whole palette of gray between getting your ass kicked and killing a guy. A lot can happen, and if you’ve decided violence is a real enough threat that you need a gun, chances are you need other skills to mitigate it as well.

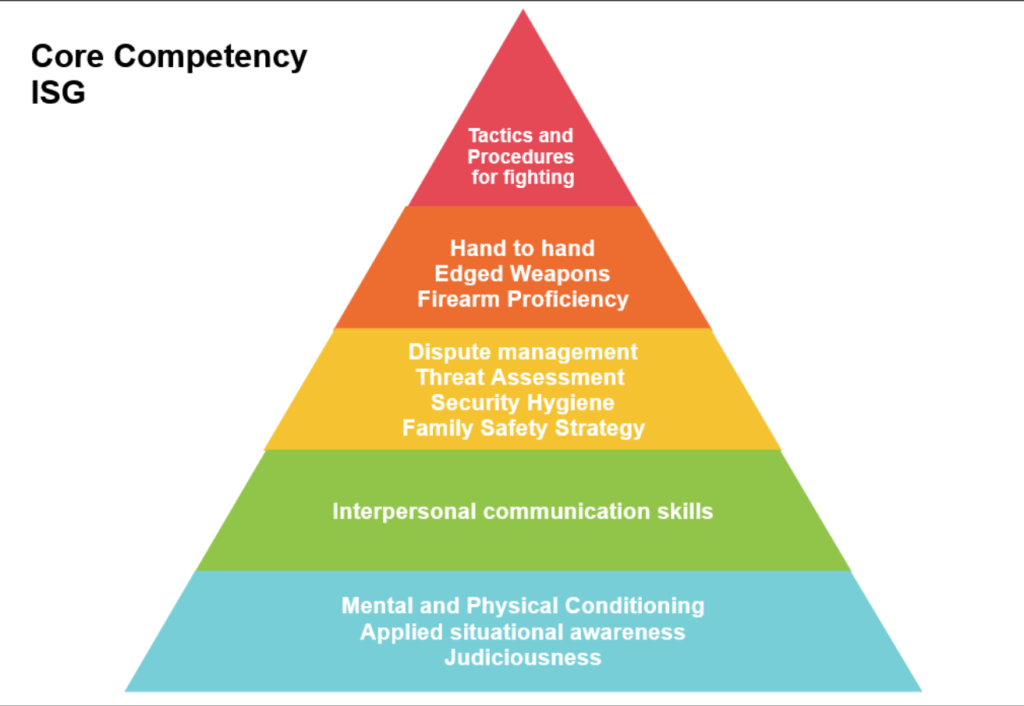

If we were to make a hierarchy like our competence pyramid above it might look more like:

Structuring your Training

When you seek training, it can be really difficult to determine who is a credible source of information.

It becomes easy to fall into the trap of idolization, and it’s also easy to expect that anyone who knows more than you is an authority.

Don’t spend too much time on credentials. What you need to do is ask “does this person have knowledge that is relevant to me?”

Remember, define the context, build the skill, then address the relevance.

Over the years, having spent some time with a variety of instructors, the ones with the most impressive resumes haven’t been the ones who’ve given the best advice for me as a citizen. A guy who can teach you dynamic entry with a carbine, but can’t lead with how to secure your home, or deter potential thieves isn’t doing you any favors. Learn from the people who know your adversary.

Conclusion

When you spend your time training, make sure that the things you do check a few boxes:

- Challenge appropriate for your skill level.

- Drills that work in judgment, communication, and environmental awareness.

- Pressure testing: train to use the skill in environments that are not ideal! Poor weather, poor lighting, fatigue, and motivated opponents are *reality*. Don’t fool yourself into thinking you will be at your best when the worst happens*, or that bad guys will just give up. They won’t.

- Establish a goal; For shooting, maybe the FAA Air Marshall’s qualification. As to medical, maybe a tourniquet deployment from pocket in under 15 seconds. With fighting, maybe train to fight for a period of 3 minutes. It’s harder than it sounds.

- Incorporate other skills into your training. How often do you check your fire when you draw your gun? How often do you apply a tourniquet after a string of fire?

- Take a class that incorporates Force on Force.

The training industry is full of bad advice. Look for instructors who will help you manage the above, and then continue to train on those things on your own. Once you’ve reached proficiency, it’s time to climb to the next level of the tower. As Paul Sharp says “New levels, new devils.” It might seem daunting, but think of it this way: when you’re on your deathbed, would you rather say you spent time pursuing things that made you stronger, more capable, a better example to your friends and family, or… you watched a lot of TV, played games, or argued on the internet? Spend time strengthening yourself. Good luck, and feel free to comment with your experience and thoughts on training… both good and bad.

Aaron