Introduction – Hope vs Hopelessness

As I sit down to write this, the world outside my windows seems mad. Utterly, hopelessly, incomprehensibly mad. You may see that, too. It seems like most people these days can sense that something, if not everything, just feels off. While it’s not the main focus of our public aspect, ISG is, principally, a cultural philosophy. At present, it feels a good deal like we’re heading into a disaster, and this wouldn’t be the first time. Throughout the ages, smug, vainglorious leadership has caused tragedy, and for better or worse, we’re on this raft together. But there is reason to have hope for our future, and we can use a few historic illustrations to guide us.

The Medusa’s Raft – The Hopeless

There is perhaps no greater tragedy in maritime disasters than the Raft of the Medusa. After weeks of smug overconfidence, the French Frigate “Medusa” ran aground off the coast of Senegal. While the passengers concerned themselves with the proximity to the notoriously dangerous shoals, the Captain issued his platitudes and assurances, confident that it was those in his care that were wrong.

The Captain, Vicsount de Chaumerey, had hardly sailed in two decades. De Chaumerey took an adversarial tone with his passengers, nearly from the outset. He chided them, talked down to them, and ignored their concerns. He was absolutely confident in his ability to navigate the Arguin bank, right up until the moment he ran the Medusa aground.

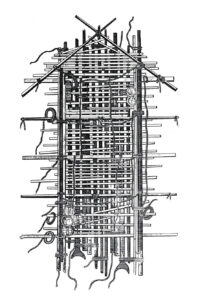

Amidst the following panic, the officers ordered 151 passengers onto a raft, promising to tow them to safety, while providing the higher class passengers a place in better provisioned boats. The raft itself, little more than slats of wood hastened together with rope, sat with its deck below sea level. It had no mast.

As the raft was filled to capacity, the weary passengers watched as the promise of rescue was horrifyingly dashed. The crew on the life boats hacked at the tether connecting them, setting the raft adrift with only the most meager provisions, almost no water, some wine, and weapons.

Hopeless and helpless to do more than watch, the makeshift raft maimed the passengers who feet slipped through the floorboards, all the while sharks circled the newly blooded water.

Resource Hysteria

The passengers of the raft consumed all their rations the first day. Among the passengers, resource hysteria was immediate, and as fighting broke out, the water rations were lost overboard.

Critic Jonathan Miles said that the scene brought the survivors to the “frontiers of human experience.” He continued, saying “Crazed, parched and starved, they slaughtered mutineers, ate their dead companions and killed the weakest.”

Whether or not…

Whether or not you’re able to see it, your life has worth. Inherent value. By virtue of being born and having free will, your existence presents to the world potential. As far back as we care to remember, we’ve been diametrically opposed to the salesmanship and vitriol of other outfits that try and sell the image of the steely eyed killer. The reason is, once exposed to that reality, to the finite, mortal world we inhabit, it’s borderline impossible to remain neutral to the cause and effect of removing that potential from the world. From snipping it off, and owning your part in taking a life. Experience is humbling.

The theater and kayfabe that surrounds the martial world is writ in fake blood smeared on prop items to ensnare the attention of the uninitiated. For sale is a simulation that, like cinema, asks a minimum of its participants: the cost of entry is suspension of disbelief and money. There are no consequences for participating in this illusion, so far as we can see, because the things we’re professing to learn are all, quite simply, abstract. For the majority of average LARP enjoyers, these things are not real, and when you take part, you’re left with no lingering philosophical questions as to your role in the act.

You’re the hero, of course.

This is important as a peripheral point, and it’s not our main topic. Discussing the theater involved ironically sets the stage for the broader story. We use it to illustrate, like tragedies in the recent past, one moment, you’re entertained… and the next, you find reality popping you in the jaw.

50’s Psychology and Hope Among Rats

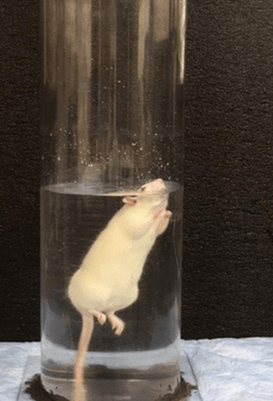

It was 1959, the heyday of pre-ethical psychological experimentation and depravity, that a Harvard researcher by the name of Curt Richter devised an experiment. If you know anything about psychology, it’s probably that researchers are tough on rats, so bear with me. Dr. Richter’s experiment was designed thusly: rats would be thrown into an inescapable vat of water and observed. Observed, they were. The good doctor timed the struggle, and found that most rats abandoned their efforts and drown after around 15 minutes.

What came next? Predictably, plucking live rats out at the last minute, just as it seemed the inescapable fate would claim the animal. Dr. Richter went about drying them off, feeding them, and allowing them to rest… Before continuing the test and throwing them back in.The results that followed, however, were less predictable.

To his surprise, the rats he had given respite continued swimming past the 15 minute mark, with some persisting as long as 60 hours.

The Andes – The Hopeful

On October 13th, 1972, Flight 571 crashed in the Chilean Andes. The aircrew had mistakenly thought they’d reached Curicó, and begun its descent. Turbulence dropped the airframe too low to recover before striking a mountain peak. The Fairchild FH227D split apart, killing 11 of the 45 passengers immediately, including the mother and sister of a young man named Fernando Parrado.

The group clung to the hope of rescue, before taking the initiative and finding the nose of the plane, and a transistor radio where they heard the news after approximately 8 days… a bulletin declared that the search was off, and the young men were presumed dead.

Upon hearing this, one of them declared to the others “Hey boys! Good news! They’ve called off the search!”

Another, stunned, called back “How in the hell is that good news?!” to which the first replied:

“Because it means we’re going to have to get out of here on our own.”

Trust vs Mistrust

Whereas those aboard the Medusa fought amongst themselves amid their desperation, the young men of the The Miracle in the Andes accepted responsibility in a stunning way. They too, were “cut loose”. The rescue was off. There would be no help. Like the raft of the Medusa, they were entirely on their own… and like the raft, they’d have to choose horrors we all hope we’ll never have to consider. The difference was that the Andean survivors were a cohesive team, used to challenges, and who trusted one another.

Back on the raft, nightly melees flared up in which the survivors ended using sabers and boarding axes to kill their rivals. In the end, the men fought tooth and nail – literally – as their weapons had fallen into the sea and the weak were killed and eaten, or thrown overboard, so as not to consume the group’s resources. It was a matter of what Eleanor Learmonth called “survivor’s math”; the process of determining who lives or dies.

“The worst is behind us, we told ourselves. We must not panic. We must stay strong for those who were seriously injured.”

– Dr. Roberto Canessa

Compare and Contrast

By contrast, the Andean survivors never considered killing the living, and were extremely reverent and respectful to their dead and dying. Instead of writing the injured off as dead, they treated their wounded… a gesture that would repay them when Fernando Parrado, previously thought to be dead, awoke from a coma.

The Andean survivors faced starvation and the horrifying prospect of cannibalism as well, they did so with the utmost respect for the living and dead. As many of the passengers were family. As well, they wasted little time. The survivors immediately made efforts towards self-rescue.

They created a visual SOS out of suitcase, made sleds, and scavenged the remains of the fuselage. Staying busy had several benefits; first, they found supplies. They made blankets and bedding out of seat cushions and luggage. The men trekked across the snowfields, which built their confidence in their mobility. Ultimately, they chose to send a small party over one of the peaks. Nando Parrado and Ernesto Canessa prepared to depart, made some emotional final gestures. In the wreckage, the survivors had found a pair of red baby’s shoes.

The groups embraced, and made a vow: They would not stop until the shoes were reunited.

The Unknown and Despair

The shoes were a Symbolon, but more importantly to us – the gesture acted as a trifecta of comforts: It honored their dead, it expressed a bond, and it defined a condition in which, even though they were apart, they were still in the fight together. The Symbolon in ancient Greece was a clay seal, broken in equal parts, and represented an unfinished transaction. In times of desperation, gestures like this carry enormous weight… and would still play a part in the outcome.

“Storms in the Andes were keeping us trapped in the fuselage. Our rugby fraternity became a family, caring for each other unconditionally and learning to pool our best ideas.”

– Dr. Roberto Canessa

“My dear, we know our business; attend to yours and be quiet. I have already twice passed the Arguin Bank… and you see I am not yet drowned.”

– Antoine Richefort, Assistant to Captain DeChaumerey of the Medusa

Parrado and Canessa (as well as Vizintin, briefly) set out, though Vizintin turned back due to lack of provisions. After a grueling climb, the two rose to a peak where they could see out into the landscape, hoping to find signs of civilization. To their horror, they fell to the ground, surrounded in all directions by mountains as far as they could see. Parrado then turned to Canessa, and said: “We’ve been through so much, and now we die together”.

Perseverance

However, Canessa refused to let his friend give up, despite his own weakness and poor health. The two decided that they could not return to the wreckage and crush the dreams of rescue for the other survivors. Knowing death would be the outcome, they continued on. After several days, the meat they’d taken from the bodies began to warm and spoil, sickening them further. Through this, they kept on until at last, they found the headwaters of a river. A cattle tender named Sergio Catalán spotted the young men, and a day later, they were rescued.

On the raft of the Medusa, it took 13 days for decimation. In under two weeks, 136 of 151 passengers had died. Of them, several more would die after rescue. The casualties in the Andean group weren’t from ‘survivors math’. Their casualties were from wounds, avalanches, and the relentless environment. The two above quotes illustrate the stark and defining contrast; the literal dividing line between life and death. We cannot overstate the criticality of these differences. Differences in leadership, in ethics, in action, and, ultimately, in outcome. The Andean survivors survived nearly 6 times longer, in an environment as bereft of sustenance.

The dynamics of their group gave them something that the Raft survivors lacked – hope.

History

History is nothing if not cruelty, hardship, tyranny, and the destructive allure of doing evil… even if your intent is trying to prevent it. Think on this in our present times.

Good, by its nature, is constructive, creative, and exists to cultivate. By virtue of this, as long as there is life, there is the potential… no, the inescapable presence of goodness. By contrast, those things that corrupt, distort, deprive, or destroy are, of their nature, destructive. They exhaust themselves as a matter of inevitability. These things cannot regenerate without introducing something good, and in time, they fail.

Leaders are Notional

While governments may have learned nothing of this, since time immemorial, we know. Those of us who’ve seen, through whatever lens, the destructive works a world bound by time thrusts upon us, know. We may not always be able to articulate it, but all the same, we have felt the touch of entropy.

It’s why our friends kill themselves, or turn to drugs or alcohol.

It’s why the Hegelian dialectic persists in an age where nearly any adult in the west has access to books. Our leaders patronize us with talk of freedom, send us to die for it, and disallow open conversation. It’s past the time to ask questions, because we’re in the inescapable bowl. It’s time to swim, but it’s not as simple as that.

The Utility of Hope

For us, the bowl is a metaphor. It’s an illusion. For the men on the Medusa, ushered onto that infernal raft, that was the bowl. Those young men who crashed in the Andes, for them, that was the bowl.

For the rat, there was no hope of escape and the outcome was inevitably death. For us, however, we are willing participants. We swim by choice, because the alternative is uncomfortable. It’s the unknown. It’s the wild corners of the map in which ancient cartographers simply scrawled “Here there be monsters.” For no matter what force attempts to convince us, the world is a vast place, and full of potential, and the hands that might throw us in the bowl are not monstrous superiors. They’re men and women, comprised of flesh and blood.

But they believe strongly in their purpose, as should you.

Another view

Our lives have been deliberately stripped of purpose, satisfaction, and the knowledge of how to change society. Those mechanisms are still there, and that too, is by design. Every few years, we frantically try and tread water like the rats, and every few years, we lie to ourselves. Cupped in the hands of false safety, we tell ourselves we’re able to rest now. Never do we question the motives of the hands.

We are like the rats in the bowl. Caught in the violent swing of politics, we may feel like we’re treading water and trying not to drown. Every few years we are cupped in the hands of false safety and allowed to dry off and get comfortable. Those same hands will throw you right back into the bowl, keen to watch you drown.

Conclusion

I wonder, at times, if things could had been different for those who found themselves aboard the raft of the Medusa. We’ve discussed all the necessary ingredients for this kind of catastrophe at length in the past. Understanding Emergencies highlights resource hysteria and competition. The Strength of the Pack tackles the importance of good leadership and cooperation. Spheres of Violence 2 discusses Realistic Conflict Theory. Could they, if they’d known, prevented their cruel fate? Could they have worked together, managed to catch birds and fish, and found ways of desalinating water with their empty casks?

History will look back on us, asking similar questions, and while we’ve discussed these topics in abstraction in the past, they are becoming ‘real’. Acknowledging the fact that we’re living in a Type III Emergency right now, and that the future will very likely look MUCH different from the past is a tough concept. It requires we suspend, in some ways, our hope that things stay the way they are. But that’s a vanity we likely cannot afford.

We can, however, put our efforts, time, and hope into building meaningful bonds with those who find themselves on the same raft. We can work to escape the bowl – or swim as hard as we can for as long as we can – if we are to make it through the troubles that are now impacting us on a daily basis. With some effort, we can drown proof our souls by knowing we’re in a dire situation, that worse is likely coming, and that emergencies, by their entropic nature, consume themselves.

Let us face these challenges with such determination as the survivors of Flight 571 when they said the cancelling of the emergency was good news. Now we know we need to rescue ourselves.

Cheers,

Aaron