In the military and martial culture, “tier 1” refers to the very best – those with the most money and best equipment. We discuss the reality: we’re ‘tier none’.

Introduction

As legions of new gun owners attempt to navigate the culture they’ve, for better or worse, stumbled into, they’re contending with a massive paradigm shift in what it means to be a gun owner.

When I was a kid, guns were still mostly about hunting. The division of younger generations of shooters who would gravitate towards cities and see guns as self defense tools was in its infancy. Now, some 25 years later, gun culture 2.0 is obsessed with all things image; they inspire one another in a never-ending circle jerk of establishing heroes, emulating said heroes, and then shit-canning them for something new and shiny.

As Jake so eloquently put in “Special Forces Worship“:

In the very online and hypothetical world of preparedness and tactical skills this sort of logic is all-too familiar. It’s a human condition that isn’t unique to our little slice of the world. It’s the same thing that makes folks buy new spandex in order to get in shape. The money spent makes them feel good, because expending the sweat is hard and takes real work.

We recognize that Tier 1 are the professional athletes of the combat world – they’re truly an elite force, and of course, are admirable. But when we consider what Tier 1 means, we also wonder if most people consider them the same way we do?

How many hours do you think candidates for CAG spend perfecting business plans? How about communications and digital security?

Do you see pictures of that? No, you don’t. Because it’s not sexy to be capable and you can’t capture competency in a <1 minute instagram video.

We know Tier 1 means badass – but we’re left with a very incomplete picture of why, so we fill in the blanks with gear and assumption… and there’s a great reason for that: Most people in the military don’t know either. They just sort of make it up as they go along.

This article isn’t about military Tiers, but it’s important to understand this going forward: When you *really* boil down what Tier 1, 2, or 3 means, it’s about how much money is spent per member of a given unit.

Tier 1 (JSOC/CAG/DEVGRU), at the top of the heap, spend an inordinate amount of money teaching their candidates and operators in such an unbelievably wide array of disciplines, your head would spin. There’s a reason these people are “special”. People at this level of the game are given a tremendous amount of trust and leeway with how they complete missions, and many of those missions remain classified for very, very long times, if they’re acknowledged at all.

Tier 2, which is still highly skilled and elite, gets a significant amount of training, but they’re still more often than not operating in a conventionally unconventional way – that is to say, “white side” Special Operations. Classified, but there’s still oversight and accountability.

Tier 3, which are elite units of the big army, still train and are highly capable, but beyond unit level training and courses that are, lets face it, largely for promotion points (Airborne, Pathfinder, etc), not a ton of money is spent sending these soldiers to develop unconventional skills.

This isn’t perfect, because there’s no universally agreed upon definitions for these, but I think it comes down to money. Few people + greater budget = more training. More training = greater cost per person.

So, where does that leave us, out here on the raggedy edge?

Right here: Tier None.

Our budget is what we can cobble together, and our schools are what peak our interest. Our efforts are self directed and often flailing, poorly contextualized, irrelevant, or just for fun.

That is, beyond words, important; because some day these skills might be necessary.

Priorities

As we discussed at length in “Collecting Hammers“, there’s an element of utility to being a generalist. The tiers above become more generalist as you ascend. The dudes working in Tier 1 are expected to know how to solve problems, and that is an utterly ambiguous task. One that is often the result of age, maturity, and experience, which is often lacking at the lower tiers (because that’s where younger troops are, to be clear).

In essence, Tier 1 Operators are capable of recreating an existence from scratch in hostile, foreign places. That’s not unique to them. Any of us can do that, albeit, with a lower budget and less skill refinement.

So let’s say from the onset – while we might not be able to match the budget or training of Tier 1 Operators, we CAN do one of two things:

- Copy what we see of their gear and equipment and delude ourselves into think that’s somehow relevant in our lives, or;

- Take what we know of the operators and their existences, and start working towards being useful in similar ways. In essence, finding our own system of tiers.

If we choose ‘Option 2’, something pretty great happens: we realize we can contextualize what we like about Tier 1, and focus on the things that are most applicable to our lives.

A Lot More Flapping and a Lot Less Flight

If we choose option 1, we’re left with a digital army of cheap knock-offs that would have us believe that their self-styling is somehow venerable. It’s really not, and no matter how uncool you are, the only thing that can make you LESS cool is being a poser.

Social media has greatly exacerbated this, and you can look upon someone’s life as a sort of highlights reel. In short, you see a lot of flapping, but witness very little flight.

Ages ago, I was in a training pipeline and witnessing all sorts of shitastic debauchery. The kind that tests your resolve in a totally different way than say, physical or intellectual exhaustion. I remember talking to one of the NCO’s about it, and he told me “Ignore these guys. Everyone who’s worth a shit is out in the field putting in work.”

This is some advice I’d like to hand along to you. The more time people have to create high-production value media of them doing things, the less time they have to put in actual, real work. Some of them have earned their retirement, but don’t forget to question the experts, and remember that we ALL have an expiration date. The ones truly worth learning from won’t hesitate to set aside their ego and explain, demonstrate, or test what they’re teaching.

Tier None: Cadre and Candidates

It stands to reason that because we have no supply chains, no doctrine, and no organization that demands testing and proficiency, that there really isn’t any cadre to teach and audit our ability… at least, not in the classical sense. However, just like comparing the open market to the military, where the profession of arms ranges from armed security at the mall to PMCs making 6 figures to do some *really* heavy lifting, there’s a gradient.

This also means that there’s advertising, pricing, and politics involved with the personalities that we select as cadre when we train. Social Media has made it boringly commonplace for institutional inbreeding to take place, and unlike military and police training, there’s rarely any true consequences for mucking up if you’re a candidate.

We’ve discussed the training mindset and how to select instructors before, but how do we audit what we’ve learned under circumstances that give us a realistic grasp on whether or not the skills we’ve learned will work in reality?

Regardless of what anyone says, training in a controlled environment is NOT the same as dealing with problems outside the script… and that grows in obviousness the more complex the situation.

The answer is we have to practice what we’ve learned on an ongoing basis, and we need to ensure we’re not finding the one thing we like and JUST doing that. For example, I *hate* Jiu Jitsu. Nothing about it appeals to me. I have friends who hate lifting weights, rappelling, camping, or whatever else, but in the end, we just have to face the fact that the stuff we don’t like doing is probably the stuff we need the most work on.

Gathering the experience through exposure is a crucial step in what’s probably the single greatest disadvantage of being Tier None:

We’re only accountable to ourselves.

Provided we uphold a high standard, that’s fine, but FAR too many people are lured into thinking that the simulation is the reality – that looking competent on IG is equivalent to being competent, not just in practice, but in actual life or death situations.

We can’t get complacent, and the idea that we train for entertainment is fine on occasion, but shouldn’t distract us from the reality that the problems we face need to be addressed as a hierarchy.

Geardos and the Cult of Hypebeast

The phenomenon above allows pretty much anyone with a gear budget and a good eye for photography and video editing celebrity status, which is all too often confused with proficiency. While some of the people in question ARE undoubtedly competent, keeping asses in classes and credit cards in hand is their ultimate job. There’s no unifying culture apart from “Appeal to the masses, have stuff, look cool”.

The problem with the hypebeast is that while THEY might be proficient, the non-contextual or irrelevant content feeds the pageant.

In this way, we can sort of define the meta of Tier None as having banished the desire to possess things or be thought of a certain way.

Looking at the daily world we live in, what use is a plate carrier and helmet with NVGs? How about pocking dumping your fruit knives and lockpicks and cultivating a ridiculous image for yourself in which you’re a reaper? (minus the whole killing people part, but shhh, IFKYK).

Clearing rooms with your GWOT traplord goons (tongue firmly in cheek) may look cool, but in what context would you be doing this, apart from the simulacra of video game-esque LARPing? If the answer is “Shut up, ISG, it’s fun” – cool. That’s perfectly valid… But button up the skills that aren’t fun, but will actually save your life first.

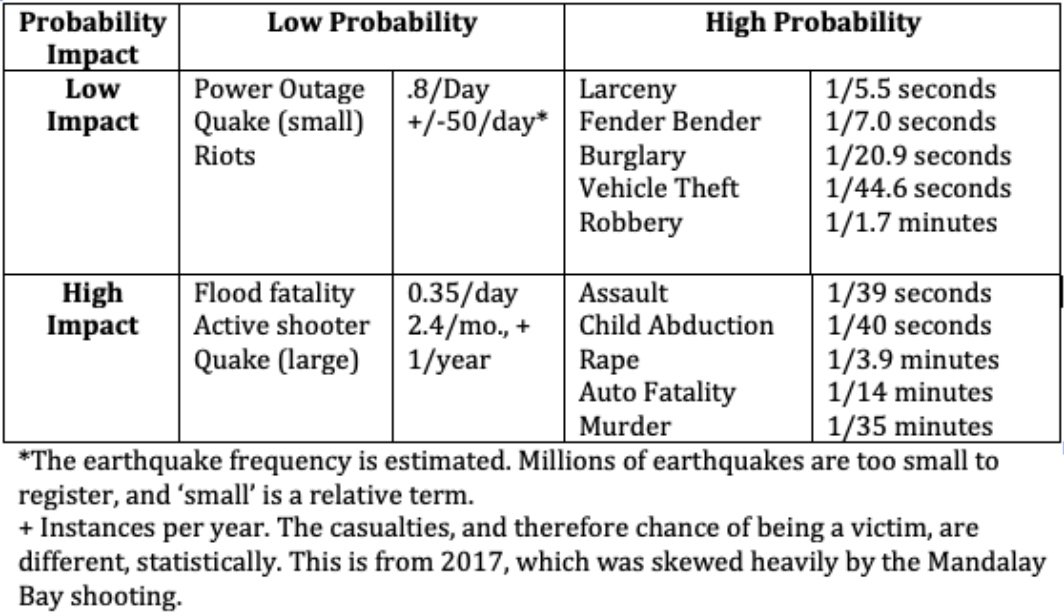

If you haven’t already, it might be a good time to print off a Punnett Square and define the likely threats you face, how often they occur, what their overall impact is, and what skills you’ll need to face them.

Conclusion

The time has come to just say it plainly. Most of us aren’t Tier One, and no matter how hard you try and emulate that world, it doesn’t change who and what you are.

The good news is that the “Special” in Special Operations isn’t just about a person’s toughness or ability – there are plenty of tough, capable people who decline military service. It’s as much about what you’re willing to sacrifice, and we all have different lines in the sand and commitments to Patria.

Secondarily, most of the training that is relevant to a well-rounded Responder Zero is available and affordable.

We often talk at ISG about what courses are the sort of ‘pre-requisites” that we like to see in people who fit in with our culture, and while there are quite a few, here are a few qualifications that really make you an asset:

- An interdisciplinary background in martial skills. Courses like Craig Douglas’s ECQC stresses many of the necessary skills, but being capable of mounting a defense against attacks is a staple of preventing victimization through time immemorial.

- The ability to stop bleeding, treat for shock, open/clear an airway, and perform CPR. Basic BCON and CPR/1st Aid can be done annually for under $250. This material needs to be revisited frequently, and medical knowledge has an expiration date.

- Technician Class HAM Radio Operations. This knowledge is extremely powerful, and it’s not easy for many people. Having received the license shows discipline, study habits, and the ability to internalize theoretical knowledge and turn it practical.

- Urban Escape and Evasion (or SERE). The ability to blend in and be the “gray man” is the sort of eye-rolling trope that many people play lip service to, but few people have any real experience with. Spend some time being hunted by humans, and it’ll quickly illustrate the necessity of being able to blend with your surroundings, keep your cool under pressure, and consider the practicality of some of the pop culture (such as improvised weapons and what it’s like to actually be abducted). This one has a lot of bullshit surrounding it, so check credentials. It’s easy to (and a challenge for) some of these nerds to play as if they know tradecraft when they really don’t. If someone won’t show you proof, pass. With this skill, I’d rather listen to someone with an arrest record who’s ran from the cops than someone who claims they know tradecraft but can’t reveal who they were.

- Have some knowledge of security – from procedures to bypass. While the ‘face’ of this is picking locks or escaping restraints, the less photogenic practices are things like how to move with vulnerable people, how to plan routes, how to secure your home or hotel, and how to identify predatory behaviors. As an aside, statistically, you’re a male between 18-55, who are certainly not the demographics most likely to be abducted. Pass these skills along to your loved ones. Our Home Security Audit is a good place to start.

- Proficiency in a Foreign Language. This shows the willingness and ability to set aside one’s interpersonal comfort and develop a skill that forces you to overcome barriers to communication. It’s difficult to keep up on in a country with a widely spoken primary language, but it speaks volumes (no pun intended) to pursue the ability to communicate with others outside your immediate culture.

- The ability to build or repair things. A trade, in short. The ability to work with your hands to create solutions or salvage failures is a tremendously valuable skill. Whether it’s vehicles, construction, plumbing, or electrical, the ability to contribute these skills in an emergency is profoundly important.

- The ability to apply traditional fieldcraft. You should know how to navigate and read a map, survive for a week without a grocery store, and be physically tough enough to deal with nature on nature’s terms. FAR too many people pose with nature as if they’re friends, without sticking around long enough for nature to bury a knife in their back. Let nature show you what you are.

- Physical fitness and personal appearance. Bottom line: your ability to be useful is related to your physical health. Many people again pay lip service to the idea of “bugging out“, but the reality is you’ll probably not be escaping the urban wasteland with your backpack and AR… But you WILL need some strength and endurance, no matter what situation presents itself.

- Take the non-sexy stuff seriously. Give thought to sanitation, water purification, and the prevention of disease/infection. Understand Emergencies, resource scarcity, and how the Spheres of Violence Change

For more on this, check out the ISG Skill Audit. Most people will score between 40-60, with the higher end being 70-80, and the lower being 30-40. Don’t worry. Life is a process, and if this seems like a lot – IT IS.

But when people go out and emulate others who are “special”, what they’re doing is mimicking the look of people who are highly capable. FAR too many people don’t realize this, but while you can’t necessarily recreate the conditions those men took to become special, you can absolutely put in the effort to build a base of skills that forge you into a useful asset, be it for daily life or dire emergencies.

There’s a final item that doesn’t make the list because it’s too important to be itemized:

ENJOY LIFE. You have less of it now than when you started reading this. Go new places, try difficult things, and don’t forget to live. Nothing about what we’re suggesting requires you live some life hiding in the shadows avoiding impending disaster. The more you get out and live, the better suited you’ll be to actually stepping up to the challenges presented by emergencies.

Do the work, and never stop learning.

Cheers,

ISG Team